What’s your Game Idea? Tactical Periodization: Building a Way to Play, Supported by a Way to Train

“The important thing is to understand the <<way of playing>> that you want to develop, and from here, to connect some principles to others, and to hierarchize them” – Vitor Frade in Martins, 2003.

Do you have a clear game idea of how you want your team to play? Okay, well maybe you have a game idea on how you want your team to play, but how close is it to the reality of how your team actually plays? What if we could uncover the methodology that integrates multiple aspects of team play inclusive of developing athlete techniques, decision making, team cohesiveness and tactics, and physiological conditioning specific to a game idea. Tactical periodization is a methodology, born in the mind of Professor Vitor Frade over 50 years ago at the University of Porto. This form of periodization is a break away from the conventional, more bio-physical based periodization models derived from Tudor Bompa (2022), Leo Matveyev (1981), or Yuri Verkoshansky’s (2009) work. Such conventional periodization models are framed around the ideas of fragmenting the physiological dimensions of performance to later piece them together, predominately focused on preparing athletes physically through exercises and training methodologies. In this way, these periodization models manipulate workloads in training to achieve a physiological “peak”, however without as detailed consideration for the periodization of technical skills, tactical decisions, team play, and their interactions with the physiological adaptations desirable to engage a broader “game idea.” Further, while existing periodization models are designed to reach an optimal level of bio-physical capabilities at a point in a given season (i.e., peak form), in team sports such as soccer, rugby, or lacrosse, could there also be a rationale for maintaining optimal or higher forms from the start of the season and throughout?

Vitor Frade’s (2003) tactical periodization fills this gap, as it is concerned with operationalizing a coach’s game idea through a set of conceptual and methodological principles that optimize technical, tactical, and physiological performances. At its essence, the logic of tactical periodization is to no longer use isolated physiological training as a means to prepare players to play the game, rather training is playing the intended game idea since day one. In other words, playing the game to be prepared for the game. This is an integrative physiology approach to training, where the collective and individual adaptability is driven by a training process where the team is interacting with the specific game patterns the coach is seeking. Each player in their specific position/role and each day designing the complexity according to the moment of the week or season. The purpose of this blog series is to present the tactical periodization methodology and its practical application. In this first blog, we present a framework for how to conceive a game idea with playing principles, from which in the next blog we will then further extend with practical methodologies and examples. We encourage the reader to apply their own interests and contexts alongside the tactical periodization concepts and principles presented in this blog post.

Conceiving the Game Idea: The Conceptual Principles

Conceptual game principles refer to “the play” or the collective intent of how the team is going to play. These principles entail “macro ideas” that guide the intent of team play in certain situations and are the main values about the way the team will attack and defend. To build this intended style of play, it becomes necessary for the coach to model the moments of the game and to have clear in his mind the macro principles that will display tendencies to achieve a collective intent. These principles should also consider the capacities of the players available to the coach.

As represented in the picture below, the situations of the game could be described as moments with or without the ball. Or, as another example, offensive organization, defensive organization, and/or transition moments.

Such a basic model can be seen below in Figure 1:

In Tactical Periodization, the game model should not be thought of as a static outline of behaviors that become layered on to the team. Rather it is something that is built along the way. The coach is tasked with beginning with the macro references or the broad ideas of the intended “play”; from which the meso and micro behaviors will emerge as they interact with the macro idea.

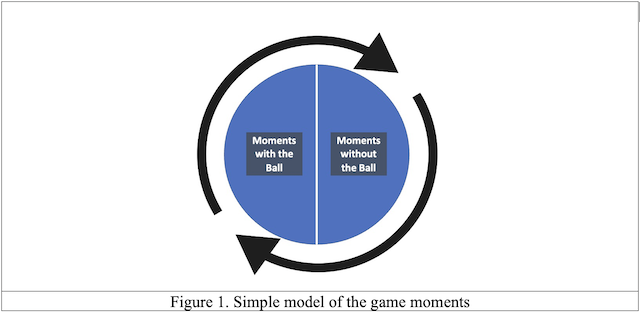

So what is an example of a macro reference or game idea principle? First, the reader should conceptualize game idea principles as an interaction of intentional and regular patterns which the team and the respective players manifest at the different scales of the team during the different moments of the game (modeled in figure 1); these macro principles therefore should consider three key factors: intentionality, fractals and articulation of sense (Figure 2).

In terms of intentionality, we argue that the most dynamic and effective principles must be open to context but limited to certain criteria. In other words, the goal is for the principle to not impose restrictions but to infer some kind of organization, a balance between freedom and order, and provide a general guide for what to do in any given scenario. So, in many ways, they are a broad guide, and should contain three key dynamic considerations: individuality, creativity, and initiative.

To engage intentionality with a game principle, it should contain the following elements:

- Individuality: allows the players to express the principles in such a way that amplifies their strengths. For example, if we are in possession of the ball and want to achieve a game principle of “progression of the ball”, our team could preference progressing the ball on the right side where our right back and right midfielder connect passes well together.

- Creativity: allows the players to achieve the objectives of the game principle through innovative solutions to situations presented in the game. For example, it is okay for players to engage the game principle of “conserving” the ball in non-conventional ways, such as the midfielder realizing that by leaving his fixed position and dropping to the right of the two center-backs allows them to keep the ball easier because the opponent left winger is late to press the ball.

- Initiative: allows the players the authority to decide individually and collectively how to act and interact through the principles. For example, if the game principle of “progressing” is not possible then engaging the principle to “conserve” until the moment to “progress” is available. Essentially, the decisions are up to the player or players, which allows them to all be on the same page as a collective group.

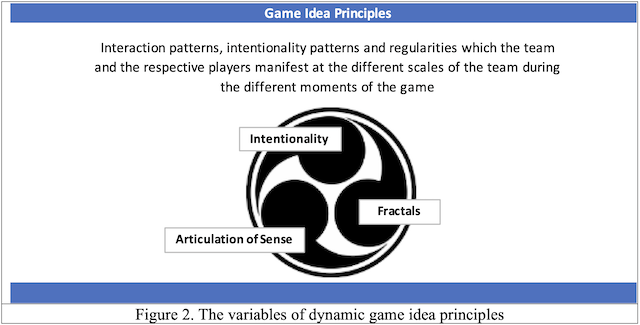

Regarding the second factor, fractals refer to the different scales of the team and defined roles in which players interact within the different moments of the game at various locations. Fractals are infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. Scales are different plans of complexity of the same skills, movements, and behaviors that occur in different sizes: large scale (big spaces, many participants and possibilities for action) and smaller scale (smaller spaces, fewer participants and possibilities of action). Essentially, fractals entail a dynamic and bi-directional relationship within a system or series of interactions. As such, there is a global progression of the ball by the team from one side to the other implying locally that players progress the ball between each other, and vice versa, there is local progression of the ball between players to engage more players down the field implying a global progression. Driven by recursion, fractals are images of dynamic systems and outline how all the players are constantly involved with different roles to engage and achieve a game principle (Figure 3).

Three scales of the game that produce different roles for players to engage the game idea principle which are of importance to note: the macro, meso, and micro scales.

- Macro: general patterns of play that characterize the team and give it its identity. For example, in the situation above, everyone has the intention (i.e., intentionality) to “progress” (i.e., principle) the ball forward.

- Meso: intermediate patterns of play that bring the macro principles to life and create the dynamics of the team. The meso scale defines the roles to achieve the macro intention. For example, roles for engaging the “progress” game principle could include moving to open spaces, passing or dribbling forward, maintaining the distance between players progressing forward together, and providing options to advancing further or more rapidly.

- Micro: emerge as a function of the dynamics between the macro and meso principles and should be conceptualized as the “unpredictability to the predictability” of the play. For example, the individual actions that occur within the micro situation to achieve the macro pattern. This may include techniques for getting open, using one foot over the other for passes, angles of support, engaging spatial awareness, dribbling maneuvers, escape skills, etc. Micro level scales are all the individual behaviors in need of being performed to achieve the game principle.

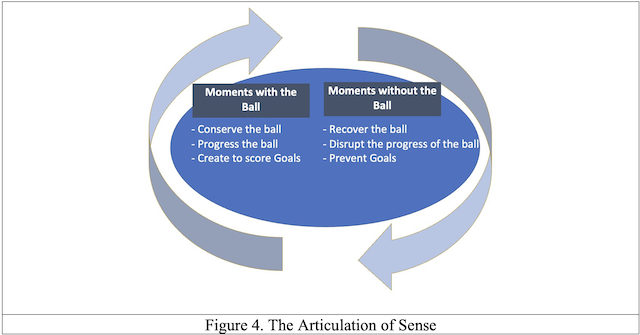

Lastly, the articulation of sense is the “adhesive” that allows the game idea principles to be in constant fluidity so that it can properly resemble the “unbreakable wholeness” of the true nature of the game. The concept of “phases” presents a sequential characteristic and a linear logic towards the game. Whereas in the game, the moments of having and not having the ball, never happen sequentially, implying that their order of occurrence is not linear. Therefore, we can infer that all these moments are connected and interdependent to each other. The articulation of sense contends that the moments with the ball (offensive organization) should not be thought of as separate from the moments without the ball (defensive organization) because they in fact condition each other reciprocally. Designing game principles that are fluid and that can transition between the different moments of the game ensures a sort of continuity to the game idea which is necessary to be effective in the game. It also ensures a balance, which prepares the team to gain and lose the ball. Figure 4 demonstrates a graphical representation of how the articulation of sense can ensure a fluidity between moments and principles. For example if the team is engaging the “conservation of the ball” principle and they lose the ball, they can quickly work together to decide if they are in a capacity to: act immediately to recover the ball, organize to disrupt any further progression of the ball or protect their goal and prevent any goal scoring chances. Likewise, if the team is engaging the principle of recovering the ball and they are able to win it back, they can collectively and fluidly decide if they are in the conditions to: finish to score a goal, progress the ball to a different area, or conserve the ball in the current ball zone.

However, reducing the analysis and understanding of the game to the division of “moments” would be equally reductive and linear, as with “phases”, its just a simple replacement of the word. What’s key to promote through the articulation of sense is language and training activities that requires the players to engage the principles of the different moments of the game in a non-sequential way, in a similar rhythm to what will be faced in the game.

This process of modelization (i.e., the shaping of the game idea) is a critical step to conceiving the game idea through the design of tailored game principles that will guide the team and players decisions and intended way of play. As long as coaches keep the three factors of intentionality, fractals and the articulation of sense at the heart of their tactical periodization design, coaches can construct a fluid way of playing that’s easily adaptable, and a game that promotes the autonomy of players in a self-organizing manner. In the next blog series, we will explore methodological approaches which operationalize the game idea through specific, yet variable and fluid practice designs and trainings tailored for developing the technical and tactical skills, and physiological conditioning to optimize game idea principles.

Interested readers are also encouraged to seek out and familiarize themselves with the official school of Tactical Periodization by Vitor Frade at https://tacticalperiodization.teachable.com/.

Reference List

Bompa, T. O., Buzzichelli, C., & Bompa, T. O. (2022). Periodization of strength training for sports. Human Kinetics.

Martins F. (2003). The tactical periodization according to Vitor Frade. More than a concept, a way of being and reflecting football [thesis]. University of Porto, Porto.

Matveyev L. (1981) Fundamentals of Sports Training. Moscow: Progress.

Tobar, J. B., & Maicel, J. (2018). Periodização Tática - Entender e Aprofundar a Metodologia que Revolucionou o Treino do Futebol. Prime Books.

Verkhoshansky, Y., & Siff, M. C. (2009). Supertraining. Verkhoshansky SSTM.