Unleashing the Power of the ACT Matrix: A Helpful Tool for Coaches to Nurture Athletes’ Mindset, Build Psychological Flexibility, and Increase Resilience

By Ryan Ford and Dr. Sara Campbell

During the spring of 2021, I had the opportunity to coach a high school varsity boys lacrosse team in Baltimore, Maryland. During one match, a feud developed between Joe, a small but feisty athlete on our team, and an opponent. Each time one of them got the ball, they battled with each other as if no one else was on the field. The fans fed into the dual like a hungry mob. It was a regular David versus Goliath battle (Joe was David). In the heat of the moment, Joe made irrational decisions, committed unnecessary fouls, displayed emotional outbursts, and ultimately performed poorly. Essentially, he replaced our team tactics with misguided effort, emotion, and ego. Unfortunately, no matter what I said or did, I couldn’t bring him back. The dual had consumed him.

Joe’s story is not unique. Throughout my time with the team, I watched our athletes get swept up in the hypercompetitive nature of sport to the detriment of their performance. The stories they created about their inferior (or superior) ability led to unethical decisions, injury, and a lack of self-control. In those moments, they needed help improving their self-awareness, emotional regulation, and response to the stressors of sport. This is not an easy process to ask anyone to go through, especially adolescent boys. However, if they did go through this process like many successful athletes have been trained to do, they would display the psychological flexibility that would allow them to invest in behaviors that were more in line with who and what was important to them.

In the search for something that could help me in this area, I discovered a simple tool named the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Matrix (Polk & Schoendorff, 2014). This tool helps athletes build self-awareness, regulate their emotions, and improve performance. It does so by helping athletes organize their experiences to create more productive and valued actions. In this blog, I’ll take you through the ACT Matrix and show you how I go about using it with athletes. I will highlight key components of the matrix so you can build it into your coaching practice.

The ACT Matrix

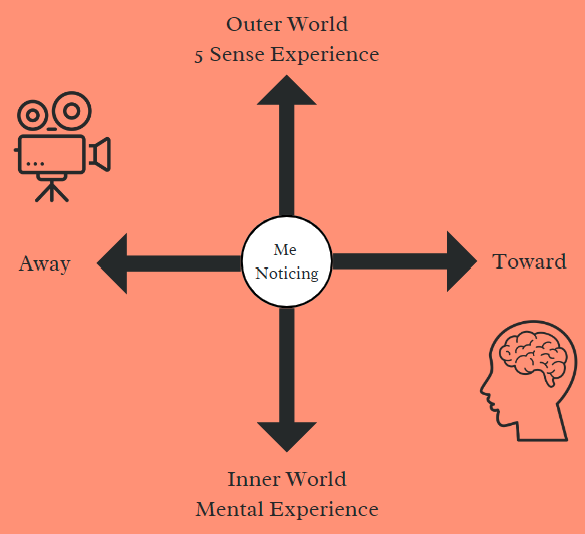

I like to think of the ACT Matrix as a lens to view one's athletic experience, or as one of my athletes so eloquently described it, “It's like putting my brain on paper.” The matrix is composed of two axis and four quadrants (see Figure 1). As athletes recall an experience, such as their thoughts leading into a championship game, they classify that experience into one or more of the four quadrants. To understand the four quadrants, athletes must first understand the x and y axes.

Figure 1

X and Y Axes of the ACT Matrix

Y-Axis: Outer World and Inner World

The south pole of the y-axis represents the inner world, or the mental experience of the athlete, while the north pole represents the outer world, or the five-sense experience of the athletes. The distinguishing factor between these two worlds is that the outer world consists of observable behaviors, meaning you, me, or anyone else could see someone doing these. Conversely, the inner world is made up of experiences that only the athlete can see for themselves. When I work with athletes, I typically begin by establishing the difference between the two worlds of the y-axis through this short activity:

Y-Axis Activity. Pick up an object that is close to you and start to examine it. Look at it closer, noticing the colors, shape, textures. Next, shift your attention to how it feels in your hand, is it rough or smooth? Afterwards, take a moment to listen to your object, you may have to create a sound by rubbing it between your hands. Continue to blend all that you have noticed together as you smell your object. Finally, if you are willing, give your object a taste. Now, what I would like you to do is put your object down and set a time for one minute on your watch or phone. During this minute, I want you to imagine in your head the object that you examined. Notice what comes up for you as you imagine this object.

The first part of this activity is designed to cue athletes into the five-sense outer world, while the second part of the activity simulates their inner world. The goal is to help them not just understand the north and south poles of the y-axis but begin to put them into practice.

X-Axis: Away and Toward

The east side of the x-axis, labeled toward, represents values, goals, and actions that move the athlete closer to who they want to be and what they want to accomplish. The west side of the axis, labeled away, signifies unwanted emotions and behaviors that prevent athletes from achieving their desired values, goals, and actions. For instance, an athlete may have identified staying calm as beneficial to their performance (towards) but may demonstrate frustration when a referee’s call doesn’t go their way, resulting in them committing another foul (away). You can even think of the x-axis as a car traveling towards its desired destination. Inevitably, there will be potholes, stop signs, and areas of construction that try to athletes away from their desired goals. However, if we can recognize these hurdles early on, we can alter our route or our car to meet our destination efficiently. Below is a story I tell to help athletes understand the x-axis.

X-Axis Activity.I was walking my dog in the park the other day when I began to take a closer look at the activity of the squirrels running around us. As I began to observe their activity, I boiled it down to two main motivations. One, they were running towards some type of food source, or two, they were running away from my dog as she chased them up a tree. Human behavior is similar. We can often be seen moving towards or away from things in the outer world but also experience this same towards or away movement in the inner world.

The Four Quadrants

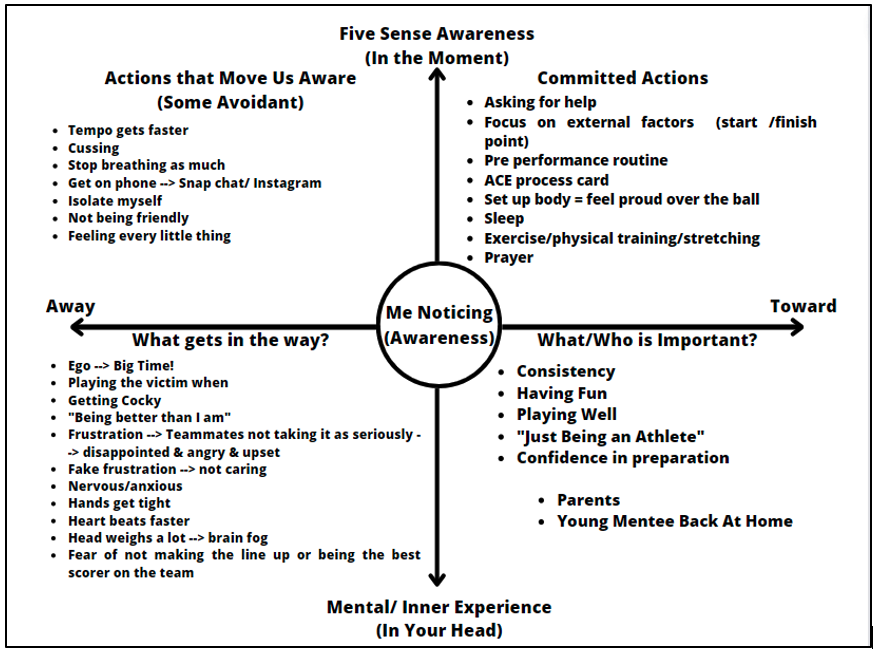

After explaining the two axes to athletes, you can move on to the four quadrants of the matrix. As you explain each quadrant, athletes can fill out that quadrant based on their experiences. I'll walk you through the four quadrants of the matrix using an example matrix created by Allison (pseudonym), a collegiate golfer that I recently coached (see Figure 2). Importantly however, each athlete's matrix will look different and can change over time.

Figure 2

Example ACT Matrix from a Collegiate Golfer

The Lower Right Quadrant

The lower right quadrant represents the athlete's inner world and toward motivations. Often, goals and values show up in this space since these are things athletes can mentally imagine and desire to move towards. The essential question to ask here is, “Who and what is important?” In the example above, you can see Allison’s values of consistency, fun, performance, and confidence. She also listed people in her life who help her move towards these values such as parents and other young golfers who look up to her.

You can facilitate the conversation further by utilizing a bullseyes activity. Here, you place the athletes' value in the center of the target and ask them to put a mark or pin that indicates how close they are to living out each value. For instance, Allison indicated that her confidence was low by placing the pin in the outer ring of the bullseye. Despite her low confidence, she indicated she was having fun by placing a mark in the center of that bullseye. Other constructs commonly explored by athletes in this quadrant include relationships, spirituality, and wellness.

The Lower Left Quadrant

The lower left quadrant represents the athlete's inner world and away motivations. The essential question here is, “What are the unwanted mental or inner experiences happening?” Often, troublesome thoughts, difficult emotions, and uncomfortable body sensations show up in this space. Our brains will create their own narratives about performance and most times they show up in a negative light. Allison identified that she often played the victim, which took her away from what was important. Her brain created a narrative that the reason she was not performing well was the fault of the course, the weather, or the opponents. She began to spiral in these thoughts and lived in a world that held no basis of reality, negatively affecting her performance on the course. Similarly, she identified her heart beating faster whenever she stood over a big putt. Focusing on how fast her heart was beating took her away from her pre-shot routine and caused her putting to suffer. By identifying these two unwanted inner world experiences, she began to build awareness of what she was going through.

A key aspect to this quadrant is supporting your athletes in understanding that nothing is wrong with these unsavory thoughts, emotions, and body sensations. In fact, identifying, communicating, and building awareness around them is a sign of strength. Being able to process how and when these experiences show up allows them to take the next step in training their mind to increase their performance. For Allison, we worked on utilizing mindfulness and breath work practices that supported her in lowering her heart rate and getting out of her head. She was able to more accurately implement mental skills to flip the switch back towards where she wanted to be. Identifying unwanted mental experiences allows coaches to train athletes to move through negative experiences more quickly.

The Upper Left Quadrant

The upper left quadrant is classified by outer world and away motivations. Because we’ve moved from the inner world quadrants (south pole) to the outer world quadrants (north pole), our focus is now on outward behaviors and actions. The essential question to ask here is, “What are the actions that move you away from who and what is important?” Often, these are avoidance behaviors that are detrimental to performance. In Allison’s case, an inability to achieve her desired values and behaviors results in self-isolation and unfriendly behaviors. Other athletes may self-harm, abuse substances, or quit sport altogether.

Importantly, the upper left quadrant is often connected to the lower left quadrant and vice versa. In the presence of negative thoughts and feelings that show up in the lower left quadrant, we participate in away behaviors from the upper left quadrant to lessen the negative inner experience. This creates a spiral effect on the left side of the quadrant that can be detrimental to performance, as athletes often get stuck in unwanted thoughts and then unproductive behaviors. perpetuates Experiences that are detrimental to performance are perpetuated and repeated when athletes continue to invest time into a behavior (upper left) that is connected to a negative inner experience (lower left). By building awareness of what is happening on this side of the quadrant, we are able to train athletes to regulate themselves when these experiences show up and instead choose a desired action.

The Upper Right Quadrant

The upper right quadrant is classified by outer world and toward. Again, we are focusing on overt behaviors here, but instead of negative behaviors, we are looking for athletes to identify desired behaviors. The essential question to ask here is, “What are the actions that you want to take towards who and what is important?” These are our committed actions and where we want to be doing the work.

Allison found she was able to get closer to the golfer she wanted to be by focusing on external factors in the outer world. More specifically, we worked on engaging in the five-sense experience, specifically touch and site, by directing her attention to the feeling of ridges on her hat and seeing the tops of trees after every shot. What this did was take her out of the fictional world her mind created about her performance that I explained earlier. Golf is a grueling sport because of how mental it is. Her new ability to dissociate between shots helped her focus on the task at hand when it mattered. Finding what works for your team and athlete is a trainable part of the athletic experience that can have significant impacts on the outcomes of performance.

Me Noticing

At the center of the matrix, you will find the label “me noticing”. The center of the matrix is where each athlete starts when they think about an experience. Many of the athletes I’ve worked with try to avoid what they are experiencing altogether or have never been asked to discuss it. They act like nothing is wrong or are completely unaware of what is going on. The matrix asks them to sit in that uncomfortable space and consider how their experience interacts with the different quadrants of the matrix.

When Allison and I started working together, I quickly recognized an increase in her self-awareness. For example, she once shared, “I noticed I was in the lower left quadrant (inner word, away) after I hit a bad drive. I was beating myself up as I walked off the tee box.” As her coach, I started to double down on this particular moment, and we explored how we could shift her to the towards side of the matrix. For example, we established performance routines that grounded her in the present moment and allowed negative self-talk to float away like clouds in the sky. This was not an easy process by any means and is still ongoing. However, the ACT matrix provided us with a way to organize what was happening, allowing for more intentional self-regulation work that was focused on context specific experiences.

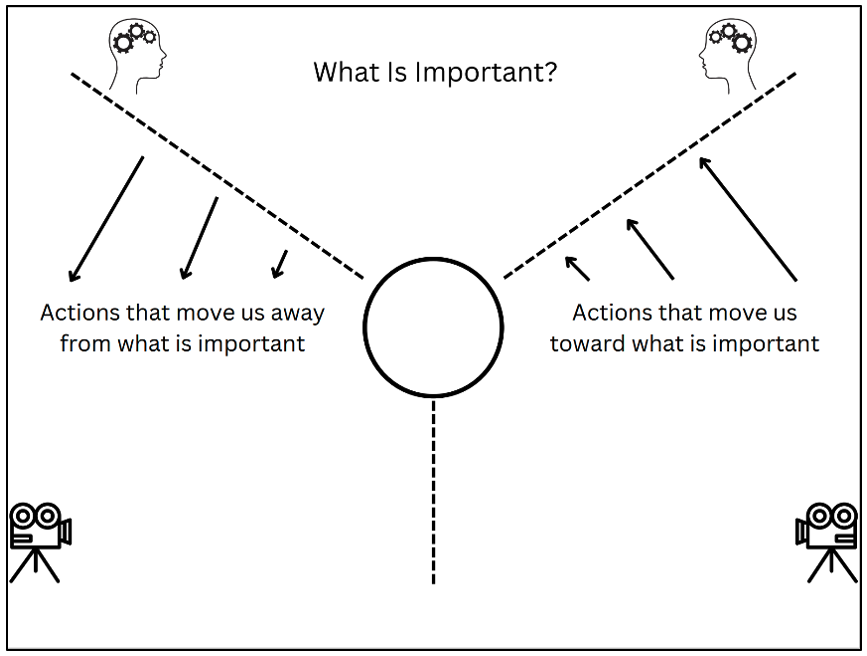

Putting it into Practice

If you decide to use the ACT matrix with your athletes, you should keep in mind that there are no wrong answers. Athletes create their matrix as coaches serve in the role of the facilitator. Be curious about the content athletes bring up and support them in continuing to build the awareness through the matrix. From there, you can begin to collaboratively brainstorm interventions that might support your athletes.

There are many ways to facilitate the use of the matrix. You could do it one on one with an athlete, or you could do it with a whole team. You could even fill out a team specific matrix. See Figure 3 below for an example of a team matrix I created. Regardless of what you choose to do, I have found that it is always best to work through the matrix in the order that I laid out for you (start with lower right quadrant and work counterclockwise.

Moreover, this tool works best when it is regularly engaged with. It is imperative that you check in with your athletes. I suggest setting up a teammate or coach check-in, asking what they noticed and how they sort through what they are experiencing. The best part about this tool is it can be integrated into activities they you already doing (team meetings or meals). Last, I would encourage coaches, parents, athletes, referees, and other sport stakeholders to consider how the matrix might be useful for themselves. Afterall, athletes are not the only ones who need to perform in sport.

Figure 3

Example of a Team ACT Matrix

Conclusion

The ACT Matrix is a tool that enhances self-awareness, increases valued action, organizes experiences, and improves psychological flexibility with athletes and teams simply by asking questions. The best part of using this tool is that it is completely flexible to the user, there are no wrong answers. The only requirement is noticing toward and away moves and sorting them onto the matrix. If we can integrate the matrix into performance environments and systems, then we will have athletes and coaches who are more aware, better at regulating themselves, and more psychologically flexible.

References

Polk, K. L., & Schoendorff, B. (Eds.). (2014). The ACT matrix: A new approach to building psychological flexibility across settings & populations. New Harbinger Publications Inc.